N B

Rocks scattered by the last breaths of the Pacific

Single channel video, sound, 2min loop

In and land eroded into

Calle Wright, Manila

2023

_

1Inside One of the World’s Longest Lockdowns

2QC, other megacities worldwide face severe flooding

3The first Trashing Palm Tree, drawn using water and a hydrophobic solution, was patterned after one from found footage of Bagyong Rolly (Category 5 Sypertyphoon Goni) by Ronel Medes.

4Gaian Assembly is a painting series featuring ‘Xerox islands’—magnified print imperfection marks resembling groups of islands—lifted from colonial-era texts about the Philippines.

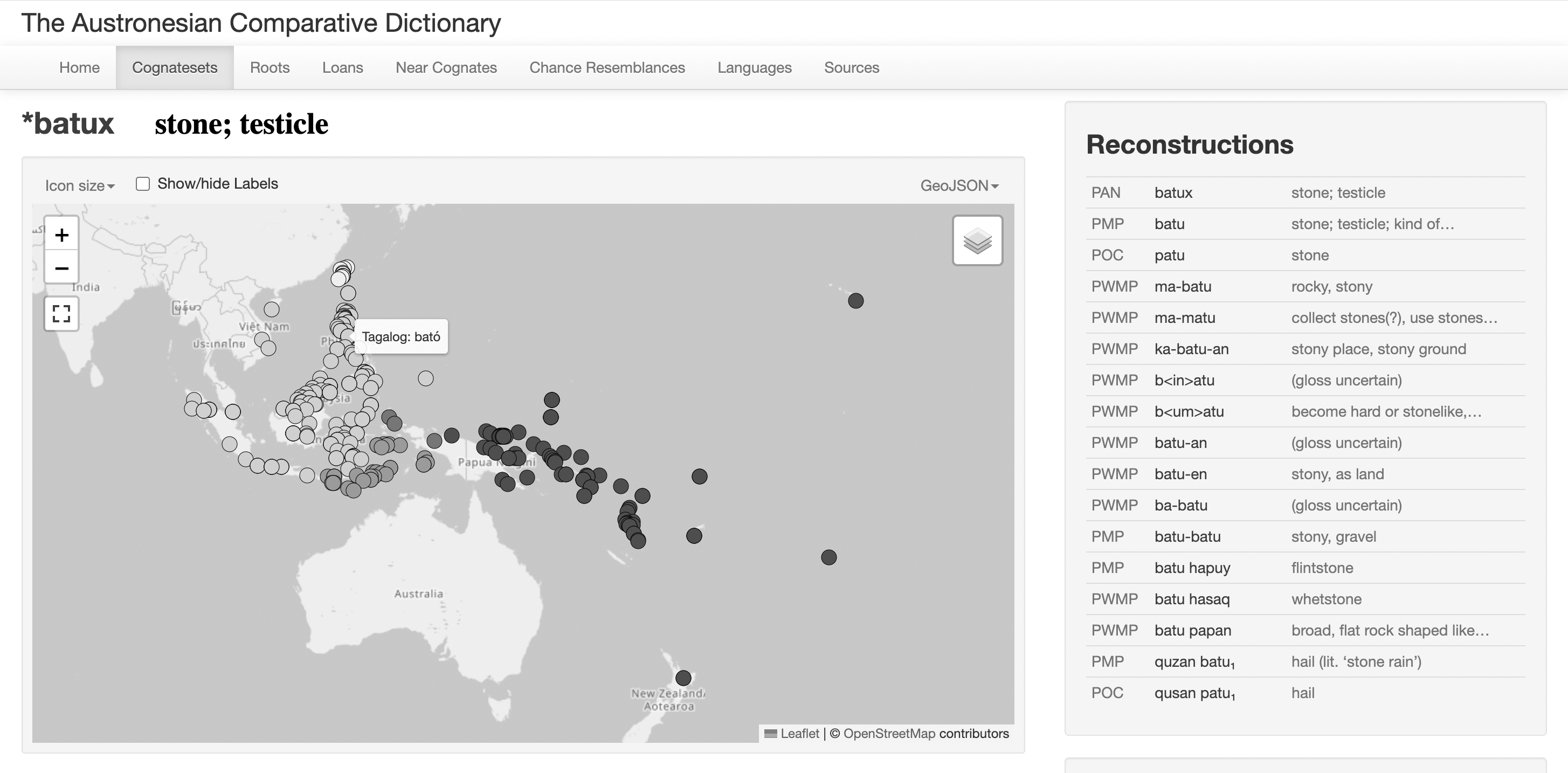

5My first encounter with batux and its cognates was in a meme.

6The Out-of-Taiwan Theory

7Measurement Of Ocean Surface Temperatures

8The New Word for World is Archipelago

9Activists have been calling on wealthy governments to deliver climate finance as grants, not loans; Centuries of colonial extraction have robbed many nations of the ability to prepare for a climate crisis they had little hand in creating... [yet] the Global South remains financially indebted to the North (Shah, 2021, It’s Freezing in LA!, p. 11)

︎︎︎The Austronesian Comparative Dictionary

Rocks scattered by the last breaths of the Pacific is, in many ways, a map. A more charismatic than accurate map, I might add. After all, it moves. Like the other faux-cartographic exercises in the exhibition, Rocks continues to reconstruct the narrative of the archipelago by way of resemblances. It takes Gaian Assembly’s4 pareidoliac conceit into linguistic territory, beginning with the serendipitous discovery of the pan-Austronesian word for ‘rock’: batux5. Across the vast latitude of the Austronesian expansion6, from Easter Island to New Zealand, the word batux has seen relatively little variation, for the larger part keeping its disyllabic structure, vowel sounds, and, more importantly, meaning. Bato in Tagalog, batu in Malay and Old Javanese, and fatu in Tuvalu all translate to ‘rock’. That these words correspond to the material makeup of islands, archipelagoes, and the crust beneath them is no coincidence. Like coconuts setting out to sea in search of foreign coasts on which to fulfill their duty to the species, prehistoric seafarers in this region, arguably less buoyant, what with batux in tow, braved the transpacific.

Some millennia later, the Pacific is no longer as forgiving. As the largest and second warmest ocean7, its tropical and subtropical zones are quite the literal hotbeds for heat-eating storms. Maritime Southeast Asia, being where it is, bears the brunt of climate change even as the crisis’ main driver, global greenhouse gas emissions, come from much larger economies8. These are essentially the same legacy economies of the Western colonial project that continue to unsustainably extract resources from here, and with the added absurdity of reverse-indebtedness through climate loans instead of grants9. In Rocks, one can observe this lasting impact of colonialism and its surviving neoimperial markets through citizen-footage of storms over rapidly warming Pacific waters in MSEA. Scattering batux around, Rocks’ premise undermines fixed positions based on language in favour of all-around borderlessness. Bato is batu is fatu. The cognates then become a kind of lexical as well as topographical motif, a layered impression of the region’s affinities, from certain colonial history to probable climatic fate.

ASSETS & ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

> Incoming Super Typhoon from the Pacific Ocean Very Scary via PhoneLovy

> Dagat ng San Jose Beach as of 10/28, Bagyong Paeng/Typhoon Paeng sa Bicol via Talipapa Channel

> Typhoon Nesat makes landfall in Taiwan via euronews (CTTO)

> Yya Antiporda

In the thick of the world’s longest lockdown1, my household suffered severe indoor flooding. Not that it was any surprise. The problem is perennial, and one that just gets worse every year2. A perceptive visitor might be able to tell by the structural oddities in the house: over a foot-high concrete barrier through the main door, a raised kitchen in an open plan. The most recent addition: a concrete-rubber combo of an elfin speed bump that supposedly seals off the gate. Supposedly. Here begins a fear of and fascination with water, stirring energies so at odds with each other it had to be contained in a drawing3.